ARISTOTLE'S WISDOM AND THE BEAUTY OF JUST OUTCOMES

HUMAN ETHICAL INTELLIGENCE IS A GLORIOUS GIFT! USE IT!!

Aristotle’s wisdom quotes

Knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom.

Excellence is an art won by training and habituation. We do not act rightly because we have virtue or excellence, but we rather have those because we have acted rightly. We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act but a habit.

It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.

Anybody can become angry – that is easy, but to be angry with the right person and to the right degree and at the right time and for the right purpose, and in the right way – that is not within everybody’s power and is not easy.

Educating the mind without educating the heart is no education at all.

Excellence is never an accident. It is always the result of high intention, sincere effort, and intelligent execution; it represents the wise choice of many alternatives - choice, not chance, determines your destiny.

Happiness is the meaning and the purpose of life, the whole aim and end of human existence.

Those who educate children well are more to be honored than they who produce them; for these only gave them life, those the art of living well.

Those who know, do. Those that understand, teach.

Pleasure in the job puts perfection in the work.

Republics decline into democracies and democracies degenerate into despotism.

Criticism is something we can avoid easily by saying nothing, doing nothing, and being nothing.

The high-minded man must care more for the truth than for what people think.1

About

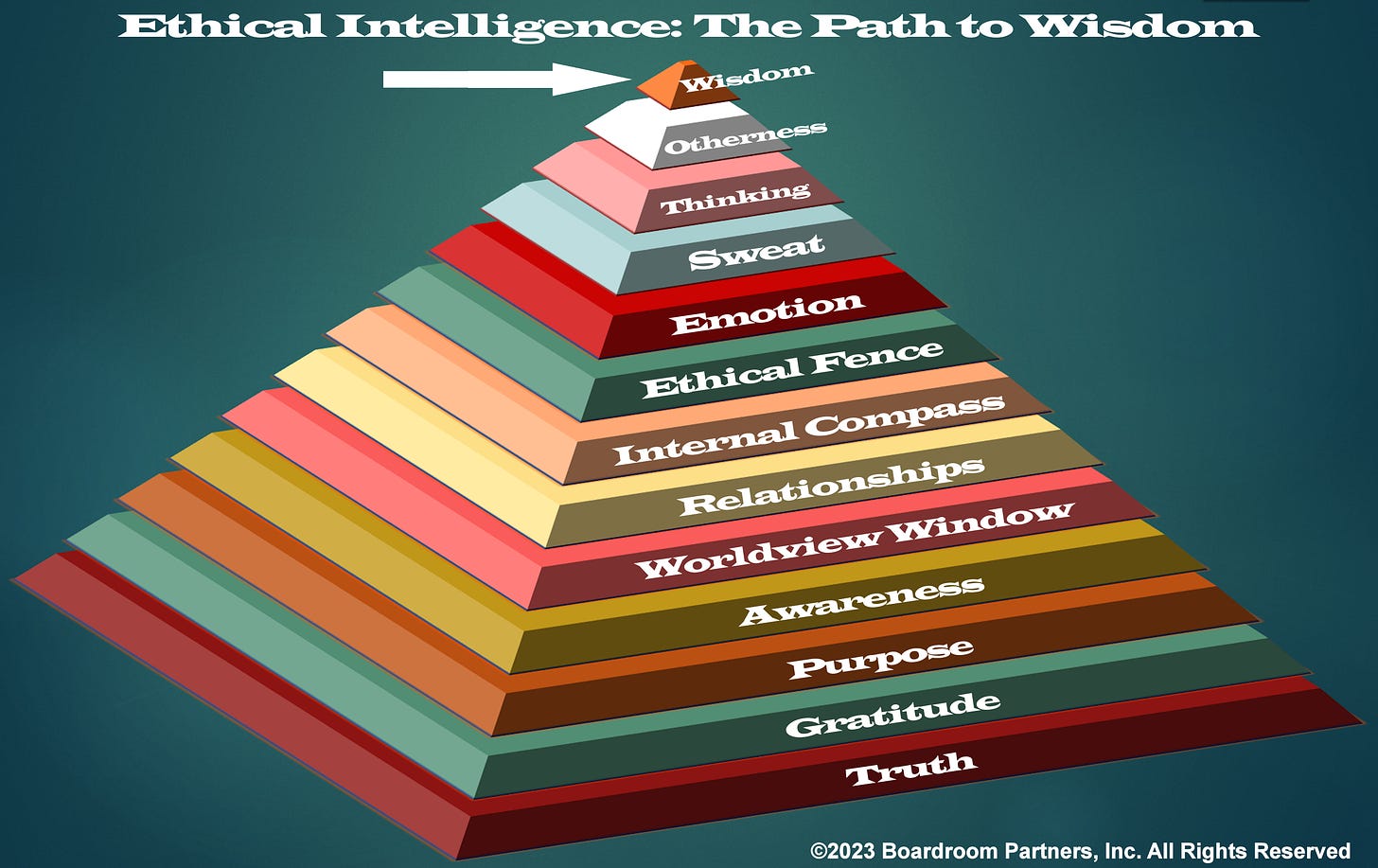

This week, we are changing our focus from foundations to our ethically intelligent life-walk objective—wisdom. We race from the base of our Ethical Intelligence Pyramid to the summit, which is wisdom.

Aristotle is one of my favorite Greek philosophers because he wrote extensively about ethics and ethical intelligence, which he called practical wisdom or phronesis.23 Aristotle’s theories about wisdom and ethics undergird much of our contemporary understanding of both. His theories about aesthetics and the beauty of correct ethical judgments have resonated through the ages.

Aesthetics and just ethical dilemma outcomes

Aristotle believed a correct ethical judgment possessed its own intrinsic beauty, and that those who lacked an aptitude for the arts were deficient in a skill essential for recognizing the rightness or goodness of an ethical judgment. At first blush, this may seem a degrading comment about those so-called “left-brained” among us. It was, in fact, a call for holistic discernment in ethical judging.

Centuries later, Augustine applied the same standard. Rejecting rules is one of the cornerstones of virtue ethics because a virtuous ethical judging approach relies on holistic discernment.4 Augustine proposed that an ethically intelligent person possessed holistic discernment and that could distinguish parts from wholes and appreciate that the beauty of the whole was often more than the sum of its components. Holistic thinking is the cornerstone of wisdom.

Wisdom is intrinsically linked to the imagination, and to beauty via the theme of fittingness. The wise person perceives and participates fittingly in the ordered beauty of creation . . . . Works of art and music provide the lighting on the stage of human existence. They also cultivate the ability imaginatively to discern certain features of our situations that cannot be perceived with the physical senses. Right perception, the capacity to discern, is therefore the connecting link between aesthetics and ethics . . . . Imagination is the ability to grasp how things fit together, the capacity for beholding wholes.5

Nearly 800 years later, Thomas Aquinas reached the same conclusions. One of the most significant aspects of Aquinas's work was the breadth of scholars from which he drew. Those included Plato, Aristotle, Ibn Rushd (an Islamic scholar), Peter Lombard, Augustine, Ulpian (a Roman jurist), apostle Paul, Plotinus, al-Ghazali (a Muslim theologian), and Moses Maimonides (a Jewish rabbinic scholar). The Summa Theologica could be considered a summation, from a Christian viewpoint, of nearly a thousand years of philosophical and religious thought spanning a wide spectrum of diverse scholarship.6

Aquinas agreed with both Aristotle and Augustine that aesthetics played an essential role in developing holistic discernment. It was that discernment, born of an appreciation of beauty that permits ambiguity, the unknown, circumstances, and context to play a role in ethical judging.7 Aquinas listed memory, insight, teachableness, acumen, reasoned judgment, foresight, circumspection, and caution as character traits one might find in an ethically intelligent person.8

Some 500 years after Aquinas, Friedrich Schiller was the philosopher who wove virtue ethics, ethical intelligence, and aesthetics together into a pleasing mosaic. Schiller lived a short life dying in 1805 at the young age of 45. During those 45 years, a man who reluctantly began his career as a military medical doctor became a prodigious poet, playwright, songwriter, and moral philosopher.

Some of his most notable works included Wilhelm Tell, the opera Don Carlos, Die Jungfrau von Orleans upon which the play Saint Joan was based, and the lyrics to Ode to Joy. Despite those impressive works, Schiller’s magnificent 1795 Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man9 (Letters) is the focal point of our discussion.

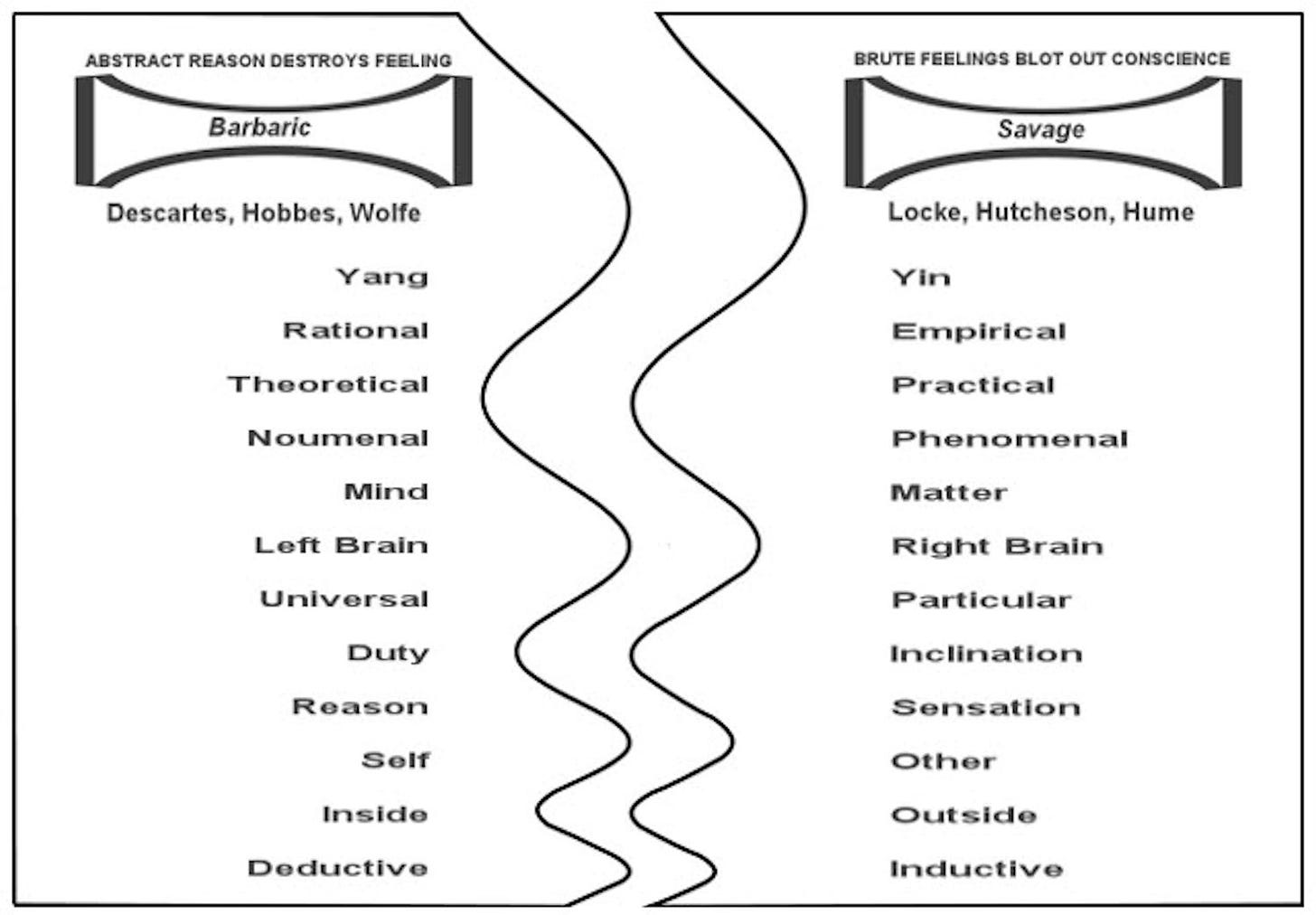

First, we must mention the Great Diremption of human nature because it has played a critical role in our current understanding of ethics and ethical intelligence.

The great diremption

By the time Schiller began compiling Letters, he had become disillusioned by the violence and bloodshed of the French Revolution. Schiller made it clear, that in his view, humanity had first to learn to serve beauty before it could faithfully serve freedom—humanity was not ready for political liberty because it was necessary to prepare for a true conception of it by first developing a sense of the beautiful.10

Schiller, an assimilator, synthesizer, and original thinker, drew on the work of Herder, Fichte, Gottsched, Lessing, Schlegel, Montesquieu, Rousseau, Burke, Mendelssohn, Hume, Novalis, and Wagner. The importance of Schiller's work was amplified not only because he was a unique hybrid of artist, poet, and philosopher but also because he was a holistic systems thinker in the spirit of the ancients such as Plato, Aristotle, and Mencius.

Schiller opposed the bifurcated view of human nature pioneered by Descartes and accentuated by those who followed, seeing in it the potential origin of the parts versus wholes problem. Schiller did not view the human person as divided into rival components such as reason and sensation, mind and matter, or inside and outside. Schiller believed in an organically whole human person. He also saw ethical judging as requiring the whole person rather than one portion or another, but he acknowledged the existing reality and described his view like this.

It was civilization itself which inflicted this wound upon modern humanity. Once the increase of empirical knowledge and more exact modes of thought, made sharper divisions between the sciences inevitable, and once the increasingly complex machinery of the state necessitated a more rigid separation of ranks and occupations, then the inner unity of human nature was severed too, and a disastrous conflict set its harmonious powers at variance.

Intuitive and speculative understanding now withdrew in hostility to take up positions in their respective fields, whose frontiers they now begin to guard with jealous mistrust; and with this confining of our activity to a particular sphere we have given ourselves a master within, who not infrequently ends by suppressing the rest of our potentialities. While in the one a riotous imagination ravages the hard-won fruits of the intellect, in another the spirit of abstraction stifles the fire at which the heart should have warmed itself and the imagination been kindled.11

Schiller thought the dream of creating a society based on pure reason had come to naught. The scientific revolution had proven to be a double-edged sword. The reduction of nature into parts, one of the hallmarks of the new science, had also been applied to human nature. The technology enabled by the latest science allowed society to engage its most malevolent desires in unprecedented destructive pursuits. Reason alone had proven ineffectual in providing a countervailing force against the tsunami of feelings unleashed by unbridled freedom.

The following depicts the bifurcated state of human nature Schiller perceived as he wrote Letters.

Schiller proposed aesthetics as a way to bridge the great divide. Plato asserted that good was beautiful, a statement with which Schiller agreed. Aristotle said ethical behavior contained inherent beauty, a declaration with which Schiller agreed. Xunzi talked about the importance of aesthetics and music for bringing Confucian order and entrance into the Way.

From those premises, Schiller reasoned that a person able to recognize beauty would also acknowledge both the good and ethical within a set of circumstances. From that reasoning came Schiller's assertion of his categorical imperative—the aesthetic education of humanity and an appreciation for the beauty of the ancients was the cornerstone for building a bridge over the great divide.

Beauty and just outcomes

The photo is what a just outcome looks like.

The just resolution of an ethical dilemma possesses an inherent beauty. It has symmetry, balance, and a satisfying aura, like the leaves in the photo. Your inner spirit has a knowing when justice appears. There is a sweetness in the air. You KNOW within your most profound being the outcome was right and just.

We rarely witness this in our postmodern society because we have abandoned holistic evaluation in favor of rules-based ethical judging. We have stopped trusting in our humanity and its ethically intelligent birthright. The whole is greater than the sum of the parts, but we no longer trust our collective judgment to see all the parts clearly.

Or, as the following illustrates, we no longer trust those we have appointed/elected to make such evaluations.

This photo is what an unjust outcome looks like.

Officials in and around East Palestine, Ohio are telling us they are following the rules. We will give them the benefit of the doubt about the veracity of their claims. As you can see, there is no beauty here. It is ugly, angry, and deadly. The company that owns this train has made political contributions to every politician and official in the state raising questions about who those officials and politicians serve.

Fish and animals are dropping dead from the air and water. People are having a hard time breathing. Yet, these “trusted” officials are telling people it is safe. There is nothing ethical, ethically intelligent, or aesthetic about this scene. We can only imagine how many unethical judgments led up to this tragic picture.

TRUST YOUR INTUITION AND IMAGINATION!!

IF IT LOOKS LIKE INJUSTICE, IT PROBABLY IS!!

What do you think?

Next week, we will continue the journey.

Remember, you cannot lie and be ethically intelligent.

Until then, Shalom!

Portions of this post were taken from my book Ethical Intelligence: The Foundation of Leadership. and/or my doctoral dissertation Exploring Ethical Intelligence Through Ancient Wisdom And The Lived Experiences Of Senior Business Leaders

References

Unless otherwise noted, quotations are taken from A-Z Quotes, Goodreads, and Brainy Quotes.

Aristotle. (350 B.C.E./2004). Nicomacean Ethics (J. A. K. Thompson, Trans.) [Book]. Penguin Books, Ltd. ((Original work published in 350 B.C.E.)

Aristotle. (350 B.C.E./1992). Eudemian Ethics: Books I, II, and VIII (2nd ed.) [Book]. Oxford University Press, Inc.

Tortorelli, K. (2005). Christology with Lonergan and Balthasar [Book]. Melrose Press.

Vanhoozer, K. J. (2011). Praising in song: Beauty and the arts. The Blackwell Companion to Christian ethics, 112-123.

Aquinas, T. (1250/1920). The Summa Theologica. In K. Knight (Ed.), The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Robert Appleton Company.

Clayton, P., & Simpson, Z. R. (2006). The Oxford Handbook Of Religion And Science [Book]. Oxford University Press, Inc.

Drees, W. B., Meisinger, H., & Liana, Z. (2006). Wisdom Or Knowledge?: Science, Theology And Cultural Dynamics [Book]. Continuum International Publishing Group.

Schiller, F. (1795). On The Aesthetic Education of Man in a Series of Letters [Book]. Dover Publications, Inc.

Snell, R. (2004). Introduction. In R. Snell & F. Schiller (Eds.), On the Aesthetic Education of Man (pp. 1-20). Dover Publications, Inc.

Schiller, F. (1795/1967). On the Aesthetic Education of Man in a Series of Letters [Book]. Oxford University Press, Inc. ((Original work published in 1795)

February 14, 2023, Volume 3, Issue 5